Windows 10 has two new icons on the taskbar. One is Microsoft Edge, the new unfinished web browser that Microsoft should have kept under wraps for a while longer. You’ve noticed that one because the “E” is intentionally designed to resemble the old Internet Explorer icon.

The other one, on the far right in the above picture, leads to the Windows Store. You’ve probably ignored it, or clicked on it once out of curiosity and then never looked at it again. That’s bad news for Microsoft, which hopes that the Store will help it build a new ecosystem that draws in developers, individuals, businesses, and game-players with a vast cornucopia of new Windows programs and apps.

It’s not going well.

You’re accustomed to using a store to find apps on your phone. Apple created a brand new business model out of thin air when it introduced the App Store for iPhones in 2008. Google followed with the Google Play Store for Android in 2012. Developers immediately rushed to create apps for iPhones and iPads and Android phones, and we were just as eager to install them. It’s second nature to turn to the stores to find apps for your phones and tablets. The numbers are staggering – the number of apps that are available, the number that are downloaded, the amount of money trading hands, all beyond imagining.

Meanwhile there was Windows, which was completely left out of this gold rush. It doesn’t occur to us to look for apps in a “Windows Store.” When we buy programs for our computers at all, it’s from Amazon or directly from companies and developers – subscriptions to Adobe Creative Cloud or Office 365, say.

In the last eight years, the market for Windows programs has slowed to a halt. Developers have been following the money and writing programs for iOS and Android instead of Windows PCs. Microsoft made a valiant effort to compete with its own mobile device platform, Windows Phone, and an accompanying (terrible) app store. That effort failed badly and at the moment Microsoft is more or less completely out of the market for mobile devices.

Since Microsoft could not compete directly with iOS and Android, the Windows Store now represents a different approach that Microsoft hopes will spark interest again in the Windows platform. Microsoft has laid the groundwork for developers to write a new generation of universal apps that run on Windows wherever it appears – computers, tablets, phones, and XBox One. It has reduced the amount of effort required to take an app originally written for iOS or Android and port it over to Windows. The idea is that developers will appreciate the simplicity that allows code to be used in all those places, and we will appreciate having apps that work consistently on all screen sizes and that we can use on all of our linked devices.

It’s a chicken and egg problem. Developers will only write interesting Windows apps if the Windows Store thrives and they can make money. We will only use the Windows Store if it has apps we want. Right now, neither side has gone first.

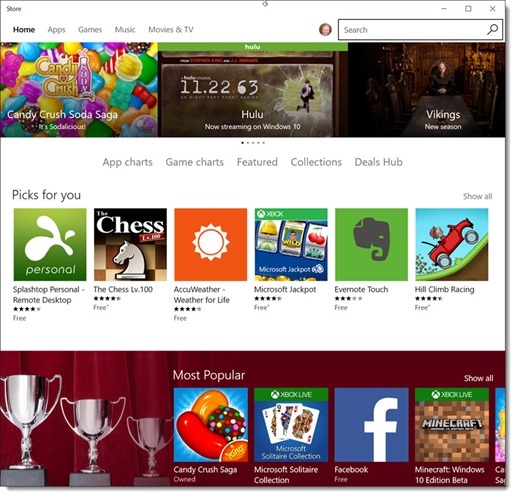

When the Windows Store first appeared in 2008, it looked terrible. Microsoft has improved the design and it’s less embarrassing now. What hasn’t changed is the thin selection of apps. There are a few flagship apps that make the front page look appealing – Facebook, Netflix, Amazon, Adobe Photoshop Express. But you will likely be disappointed when you try to go one step further. You’ll look in vain for Instagram, Snapchat, or, well, basically anything else you can think of. For the most part you’ll find bad games and knockoffs of apps that are better on iOS and Android.

At the moment Microsoft does not allow any traditional Windows program to be sold through the Store, only new “modern” apps, the ones that don’t look like the traditional Windows programs you’re used to. Under the hood they have some nice features to make them scale nicely to different size screens and to make them more secure. But you’re not used to looking for modern apps and the ones that have appeared are not very compelling.

There are two recent examples that you actually might want to look at. Dropbox and Box have both released Windows 10 apps that are separate from and in addition to their other Windows apps. Each one gives you the ability to browse through files stored online, regardless of whether the files are synced to your local computer. You can open files for editing from the apps, then save files directly back to online storage.

The Box and Dropbox apps are nice but each one has the same problem shared by many other new “modern” Windows apps: the experience is far more limited than what you can get by going directly to the websites. There are fewer controls, fewer options, and many missing features, compared to the websites for the services. The same thing is true of all too many other new universal Windows apps. There are Windows apps for TripAdvisor, Spotify, Facebook, and others that are not much more than wrappers for some – but not all – of the website content.

There are other universal apps that roughly translate a traditional Windows program into the new programming environment – OneNote, Evernote, or Skype, for example. The best of them are fine but at best they are almost as good as the traditional programs, never better than the originals.

The result is the perception that the Windows Store is failing. Developers tell stories of making apps that are perceived as being popular, like NextGen Reader (a quite good RSS reader), and making next to nothing in the Windows Store. A well-known developer had a post go viral on Reddit when he suggested that developers should give up on Windows. “Since Windows 10 arrived, the sales of all of my apps, which have been very low compared to other apps stores, have gone down significantly, nearly to zero (even the one I upgraded to Windows 10),” he wrote.

Meanwhile, there are frequent complaints in the tech community looking at the Windows Store from the perspective of users. Paul Thurrott summed it up recently: “There’s just no there … there. It is the most lackluster of the big app stores (including Apple’s and Google’s), with the fewest apps and games, the fewest high-quality apps and games, and the most woeful presentation to the user.”

All is not lost. Microsoft is spending freely to entice developers to build universal apps to Windows and the results are slowly starting to appear. It had to buy the company to do it but the Wunderlist to-do app is quite good. I use several universal apps – NextGen Reader, Tweetium for reading Twitter, Adobe Photoshop Express, Plex for accessing my media library when I’m away from home. There are no new traditional desktop Windows programs coming (that market is dead), so if you’re going to do anything new with a computer, chances are it will be done with a universal app from the Windows Store. Microsoft is overdue to provide tools for developers to help them make Windows 10 apps that are better than old-fashioned programs and better than visiting a website.

There are two areas that might not affect you directly but could make the Windows Store successful.

One is apps directed at enterprises. The Store is set up so enterprise customers can create custom portals for employees to install approved apps on their devices. HP introduced a new device at a trade show this week, the HP Elite X3. It is a Windows phone that can turn into a computer when it is attached to a special docking station. It will only run universal Windows apps but HP is doing some clever things so employees can access their traditional line-of-business programs. (It’s complicated. Let’s call it a very specialized version of Remote Desktop and leave it at that.) There are no plans to sell it directly to the public; it is for enterprises only. No one knows if it will be successful but HP has invested heavily in the effort and it gives you an idea of the kinds of things that might help keep Microsoft profitable even as it fades out of your view.

The other potential win for the Windows Store is in the world of games. PC gaming is a hotly competitive field dominated by Steam, which drove out competing services (including Microsoft, which had tried to compete with its Games For Windows Live platform) and took over PC game distribution almost singlehandedly. Now Microsoft is trying to break into that monopoly and take back some of the gaming market. Microsoft has written the universal app framework for developers so the same game code can run on both a Windows 10 PC and on an XBox One in the living room. That’s brand new but still untested. Meanwhile Microsoft is trying to get out its message by convincing big game developers to write marquee titles as universal apps – for example, Rise Of The Tomb Raider became the first major game released through the Windows Store when it appeared a few weeks ago, although it is also available through Steam and no sales figures are available to show if Microsoft is taking away much of the market. Even more aggressively, the PC version of at least one upcoming game, Quantum Break, will be exclusively available through the Windows Store, which has the gaming community all aflutter. Gamers live in a very specialized world that is opaque to outsiders so there is no way to predict how that effort will turn out for Microsoft.

There’s no lesson here, nothing to be avoided, nothing to get excited about. In the next year or two, if you read about a useful Windows app, try to remember that there’s an app store in Windows 10. It’s the icon you took off your taskbar because it wasn’t very interesting.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks